Raise your children with a love of science, and there’s a decent chance they’ll grow up wanting to be like Richard Feynman, Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, or any number of other famous scientists from history. Luckily for them, they won’t yet have learned that the pursuit of such a career will almost certainly entail grinding out a PhD thesis. But it’s also lucky for you that they consequently won’t ask you to explain the subjects of their idols’ theses. Maybe you tell them about quantum electrodynamics, radiation, and even the theory of relativity, but what can you recall of “The Principle of Least Action in Quantum Mechanics,” “Research on Radioactive Substances,” or “Eine neue Bestimmung der Moleküldimensionen”?

Perhaps “recall” isn’t quite the word. But if you want to get a handle on these papers, which constitute important parts of the foundation of the research that would ultimately make their authors famous, you could do much worse than beginning with the explanations of science YouTuber Toby Hendy. In recent years, while building up an ever-larger audience with her channel Tibees, she’s occasionally reached into the archives and pulled out a notable scientist’s PhD thesis.

We’ve assembled all of her videos in that series into the playlist above, which also includes Hendy explanations of theses written by figures not primarily known to the public for their research: Carl Sagan and Neil DeGrasse Tyson, and Brian Cox (the physicist, not the Succession star), whose media work has inspired generations of fans to go into science.

Though a young woman, Hendy has mastered old-school teaching techniques, such as drawing on a transparency placed on an overhead projector, that may trigger Proustian memories of science class, at least in those of us of a certain age. With her calmness and clarity (not to mention her willingness to admit when she herself struggles with the material) she’d surely have ranked among any of our favorite teachers, and if you introduce her channel to your kids, she’ll probably become one of theirs. Whether they go on to earn a science PhD is, of course, down to their own inclination and efforts. Like so many young people these days, they may ultimately come away with a stronger desire to become a YouTuber — which, after all, is what Hendy quit her own PhD to do.

Related content:

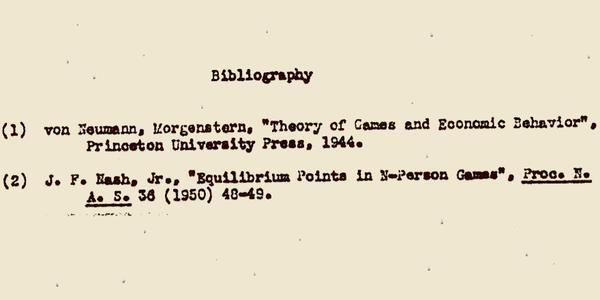

John Nash’s Super Short PhD Thesis: 26 Pages & Two Citations

Queen Guitarist Brian May Is Also an Astrophysicist: Read His PhD Thesis Online

Albert Einstein’s Grades: A Fascinating Look at His Report Cards

This Is What an 1869 MIT Entrance Exam Looks Like: Could You Have Passed the Test?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.